“She [Mary] wrote to the members of the Council and to the Principals of the Realm expressing her astonishment at their not coming unto her to do homage as to their true and lawful Queen and successor to the Reign. In the meantime she started levying a few men, calling to her support many Nobles of that Kingdom, to protect her against the force of the Duke.”

(Giovanni Francesco Commendone, Successi d’ Inghilterra, 1554)

“Declaring to them my insufficiency, I greatly bewailed myself for the death of so noble a prince, and at the same time, turned myself to God, humbly praying and beseeching him, that if what was given to me was rightly and lawfully mine, his divine Majesty would grant me such grace and spirit that I might govern it to his glory and service and to the advantage of this realm.”

(Jane Grey’s account of learning the news of Edward VI’s death and her own accession)

Reports that the duke had dispatched an army headed by his son Robert to capture Mary and stop her supporters from getting to her, must now have been known to the lady in question. Thomas Hungate, her servant who had volunteered to deliver to the Council a letter declaring her accession and warning them against supporting Jane, understood the possibility of being captured en route. Fortunately he would succeed in his mission. But his joy would be tempered by his consequent imprisonment. In twenty-four hours time, Hungate would be arrested and taken to the Tower. Later the Council threatened to have various Catholic prisoners in the same facility, amongst them Stephen Gardiner and Edward Courtenay, earl of Devon, executed if Mary persisted in her defiance of Edward VI’s wishes. Mary ignored them.

Letters calling for support were dispatched to allies. The peers of the realm were also advised to cast aside Jane and join Mary, a decision which most did not immediately take. One man, Henry Ratcliffe, second earl of Sussex, was uncertain of what course of action to follow. A conservative in religion, he felt sympathy for Mary’s position. But it was one thing to pity the princess and quite another to support her and oppose the Council who controlled the treasury, the royal fleets, numerous strongholds and of course the capital itself. He later claimed that Robert Dudley, the same man searching out Norfolk for Mary, told him the king was still alive and that Mary was a traitoress attempting to usurp her brother’s throne and deceiving others into aiding her. Understanding Sussex’s reluctance, Mary would soon force his hand by taking as hostage an individual whose welfare Sussex was utterly concerned for.

For some men, Mary’s letters requesting support were unnecessary. They rushed to Kenninghall and offered their assistance unreservedly. They brought arms and had called upon the support of neighbours. Such was the case with Sir Edward Hastings who was described by opponents as a ‘

hardened and detestable papist’. Having received his summons from Mary on this date, he proceeded to raise troops in the Thames Valley. Soon he, Lord Windsor and Sir Edmund Peckham would be proclaiming Mary queen in Buckinghamshire, securing the county for her. Generally, Norfolk proved to be Mary’s county. Indeed it seems the whole of East Anglia was sympathetic towards the princess’s cause. This may seem odd at first given that Protestantism had entrenched itself in these parts. Most of the Protestant martyrs of Mary’s reign derived from the east of the kingdom and the rebels of Kett’s uprising of 1549 had made it clear their point of discontent was with Edwardian economic policies, not religious. Yet these same individuals had not forgotten the way they had been dealt with by the government during the events of 1549. The rebels had been utterly suppressed and this persecution, committed only four years previously, was still fresh in the minds of all. Additionally and perhaps most importantly, the man who had been instrumental in destroying the rebellion – the man whose army had defeated the rebels at the battle of Dussindale and caused around 2000 casualties – was none other than John Dudley, duke of Northumberland.

So far in this account of Mary’s course to the throne, one individual important to the events has not been mentioned. The lady in question was just as affected by Edward’s ‘

Devise’ as Mary but her name is often overlooked in accounts of this episode. Elizabeth, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn was once again declared unfit to rule owing to her illegitimacy. Elizabeth had never known a time in her life when she was considered the King’s lawful issue, having been only two when her mother was executed and her father declared her to be his second bastard daughter – the product of another union that was allegedly offensive to God. But like her sister, she was observant and protective of her rights awarded to her in the 1544 Act of Succession and her father’s will. By July 1553 she, along with Mary, was the richest woman in the realm and owned a mass of properties. Like Mary she had been present at one of her own manors when Edward died and like her sister she headed a household devoted to her. But aside from voicing indignation about her brother’s plans, Elizabeth could do very little. She stayed in her household at Hatfield and waited – waited for her sister to succeed; waited for her to fail. As queen, Elizabeth would display unbelievable courage and temerity which matched that exuded by her brilliant parents. But she was indecisive and often reluctant to take a firm stance on certain issues out of fear of the consequences. Only a year later she would take a similar position whilst the rebels of Wyatt’s revolt acted against Mary. Elizabeth was not made of the stuff of martyrs and had her own survival in mind. Her concern was hardly unreasonable or cowardly. Mary too had known times when she would balk in the face of adversity and she would conform, even if it defied her principals, so she could persevere. When Jane’s cause had finally been crushed and the sisters met outside the gates of London, Mary would show no anger or hurt over her sister’s decision to remain quiet in the early days of this troublesome time. But maybe a tiny thread of doubt crept into her mind; a thread which would be spun into something more substantial with every real or supposed act of discontent Elizabeth would later make.

Meanwhile nearer to London, the hapless Jane Grey was finally informed that she was now queen. She had been residing at Chelsea Manor when, on this date, her sister in-law, Mary Sidney (the wife of one of the men present at Edward’s deathbed), told her the news of the King’s death and that she must now go with her to the former abbey at Syon where she would be attended by the duke and other peers. Yet when she got there the men were not present, fuelling Jane’s confusion. Before long, the duke of Northumberland, the marquis of Northampton, the earl of Arundel, the earl of Huntingdon and the earl of Pembroke walked in and informed her of the king’s demise and her own accession. “

Which things, as soon as I had heard, with infinite grief of mind, how I was beside myself stupified and troubled”, she later told Mary. After displaying concern about Edward’s changes to the succession and her own ability to govern, she accepted the Crown. If God had called her for this task who was she to question His plans? It was nearly time for her to be taken to London and displayed in public as the queen. She would go from Syon to the Tower, a route also taken by Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Katherine Howard, some eleven years before her. Unfortunately the similarities between the pair do not end there.

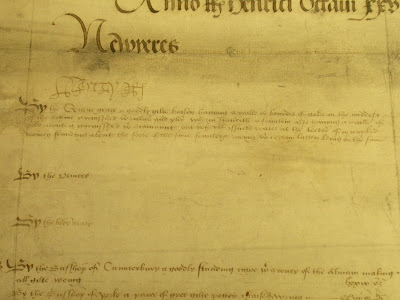

(Image -

Engraving entitled, "Lady Jane Grey Declining The Crown" by Robert Smirke, 1860).